Importance of Setar in Iran Culture

Setar is an ancient musical instrument used for centuries to express art, identity and is central to Iran’s diverse cultural fabric. Among the earliest stringed instruments from Persia, the setar’s history is entwined with the songs of the old courts, developing throughout dynasties to become a symbol of Iranian musical culture. The setar embodies Persian musical traditions with its unique design, complex playing style, and significant influence on classical and modern music. Understanding Iran’s musical landscape is shaped by investigating the historical origins, distinctive construction, playing methods, and changing role of the setar. Melodies of the present and tales from the past reverberate through its strings. Therefore, the setar serves as a bridge between generations in addition to being a musical instrument that emerged from the Persian- Iranian culture. Apart from cultural value, the setar is considered a magical musical instrument that also has emotional value to the people of Iran (Sala Muzik).

Origin and Background of Setar

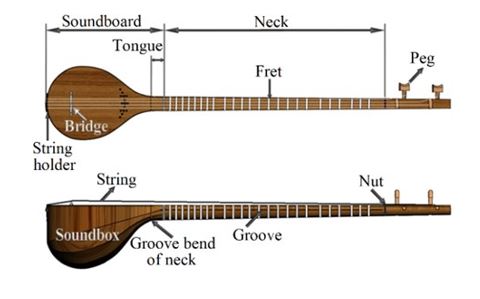

The setar is an Iranian string instrument featuring four metal strings and a small soundbox shaped like a pear. This musical instrument, which belongs to the long-necked lute family, produces its first sound through the vibration of a stretched string. The Persian word “setar” originally meant “three strings” (‘se’ meaning three and ‘tar’ representing string) (Pedrammehr et al., 2681). However, an artist named Moshtaq later added a fourth string that is why the fourth string is called Moshtaq. The setar has multiple tuning sets based on which Dastgah (mode) it is to be performed. Like the Tar, the last string is typically one octave lower. Setars have long necks with twenty-five gut frets connected to the resonating box. Walnut trees make the neck, and mulberry wood makes the soundbox. The long neck lute makes us believe this instrument is related to tanbur and dotar (Week Lecture 3).

There are approximately twenty scale degrees in the setar’s melodic range. In the last thirty years, two renowned master performers, Mohammad-Reza Lotfi, and Hossein Alizadeh, have brought new techniques to setar playing, revitalizing it rather than using the traditional way of playing it with the right index finger’s nail. These techniques have made setar to be considered one of the supreme instruments used in performing Persian classical music. The instrument has contributed to the evolution of new contemporary compositions including approaches to melodies. Despite tar instrument increasing popularity because of its size and “fuller” sound setar has opened the door to Persian classical music boundaries. Many young musicians and instrument makers have fallen in love with setar and Persian classical music enthusiasts have recently emerged bringing the instrument back to public attention (Taghavi 2015).

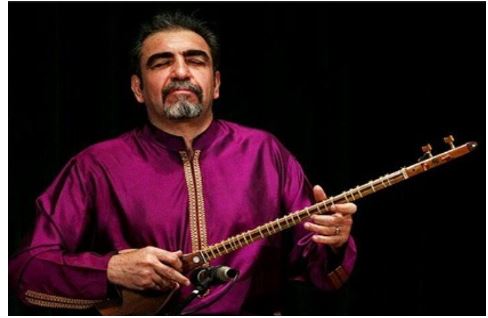

Fig 1: Setar

Schematic View and Sound Performance of Setar

The setar was popularly used to play Dastgah; Persian classical music and it was played on the tip of the long nail of the index finger strumming it up and down. Both the melody and drone are produced when it is strung. Though it usually has a gentle tone, setar occasionally has a loud, robust sound. Figure 2, describes a schematic of a setar and we discovered that the most important part is the soundbox which consists of a flat plate with a pear-shaped bowl. Both the bowl and the soundbox are made of wood but the bowl has unique features; bent ribs glued together (Mansour et al., 1738). Setar’s fretboard features 22 to 28 movable frets that can produce unique tones. Regarding dimensions, a sound box’s average range is between 22 and 30 cm. The fingerboard has a range of 40 cm to 48 cm in length. The fingerboard measures three to five centimeters wide (Pedrammehr et al., 2681).

Fig 2: Setar’s schematic view

The Persian Setar soundbox size determines the classification of two setar models; the Kamaliyan and Hashemi. The Kamaliyan model has a large soundbox and produces a bass sound while the Hashemi model has a small soundbox but produces a higher sound. The present Setar is remarkably similar to the instrument of a musician depicted in clay statues discovered in the Haft Tape and the temple of Choqar Zanbil in the province of Khuzestan. The tanbur was an instrument used in that era. Numerous poets from Iran who lived centuries ago used the word “setar.” Farabi mentions the tanbur in his well-known work, Musiqi al-Kabir, written over a millennium ago. The school thoroughly describes the many varieties of Iranian tanbur in this book. The resemblance between these tanburs and the current setar indicates that the latter is descended from the former. Played with all fingers of the hand, the tanbur is considered the ancestor of the setar. From the beginning, this is how it has always been played. The setar is the only instrument made in Iran that is played with the nail. There is a little history behind this setar playing technique. The Safavid-era paintings in Esfahan’s Chehelsotun Building depict an instrument resembling a setar with six strings instead of just one (Farabi School).

With the founding of Iranian Radio, the setar playing style was altered. In 1948, Esmail Navab Safa invited Ahmad Ebadi, the youngest son of Mirza Abdollah, to the radio. Despite studying the traditional setar playing technique, Ebadi created a new method that involved playing just one string at a time. People would hear this particular setar playing style on the radio. Following the passing of Master Saba, the traditional setar playing method was not adhered to. Setar players have started using this instrument in their unique ways that keep attracting young musicians. New instruments that draw inspiration from the setar model have been developed recently. Arsalan Dargahi’s creation of a skinned setar at the start of the 20th century was the first example of this experience. This type of setar has a slightly tar-like voice due to its skin. Other recent innovations include the shurangiz and bass setar. But the setar has become more well-known than any of the other instruments. The shuranqiz has a deeper, more bass-heavy sound than a regular setar. Its four strings are similar to those of the setar. The six strings on the larger ones are divided into two pairs (Farabi School).

The setar has encountered many situations since the turn of the 20th century. As a result, about ten distinct approaches to playing this instrument have been developed. The more recent performers’ styles and those from the past impact the more recent ones. The primary distinctions are between how the various techniques are played, the frets on the fingerboard being touched, and the method of striking the string with the tip of the nail. Additional factors influencing the sound quality produced by the setar include playing all the lines simultaneously, playing one string at a time, or playing in the tanbur style. But unlike tanbur, setar produces soft timbre which sometimes becomes loud and vigorous. Physically, this instrument has a small, curved body with an extended fingerboard. It has four metal strings, that is, two single cords and one double, tuned to C, G, and C. The cords make the instrument tunable in different modes (Ardalan 13).

Additionally, a setar tuned one octave lower than a standard setar is called a bass setar. Invented by Masoud Shoari, the bass setar is occasionally performed in ensembles. A brand-new instrument known as the salaneh was created recently; it was modeled after the oud and setar and shares many of their tonal qualities. Given that the nail tip is used to play the salaneh, it bears similarities to the setar. Its upper register has a setar like sound as well. The salaneh has six main strings and a few drone strings fastened to the instrument’s body. These drone strings simply amplify the instrument’s natural sound. The setar has been more involved in public and group musical works in recent years thanks to technological advancements. Jalal Zolfonun formed a group of setars in the 1980s. Only a few setars were present in this group, along with percussion instruments like the daf and tonbak. Virtuoso setar players have recently demonstrated new abilities with their device through solos, which differ significantly from traditional setar compositions. For instance, Hussein Alizadeh’s “Turkmen” is an entirely original setar playing style that does not necessarily fit within the Persian radif (Farabi School).

Iran’s musical legacy, intertwined with innovation and tradition, resonates with ageless significance in the echoes of the setar’s strings. With each pluck and slide bearing the weight of centuries of creative expression, the instrument’s journey through the ages reveals a dynamic interplay between preservation and evolution. The setar, with roots in ancient Persia, has served as a cultural symbol and a vehicle for the narratives, feelings, and complex melodies that characterize Iranian music ever since. The skill with which it is played, honed over many generations, enables performers to express the subtleties of Persian musical modes in a way that cuts beyond language barriers and speaks straight to the heart. The Setar continues to be an essential link between Iranian musical traditions’ past, present, and future, even as it evolves to incorporate modern influences. The instrument has enabled Iranians to understand their culture’s history of art and it gives young people a wonderful opportunity to play and have a connection with their ancestors (Sala Muzik). In general, setar remains a cultural treasure and national heritage to the Persian people and as part of their identity. Some of the prominent Iranian setar players we learned in class include;

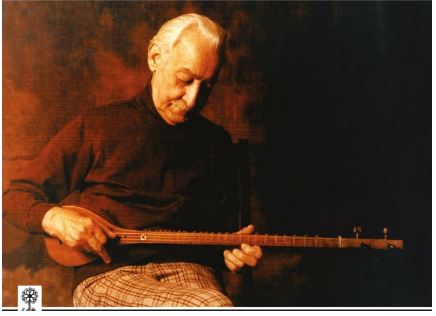

Fig 3: Ahmad Ebad

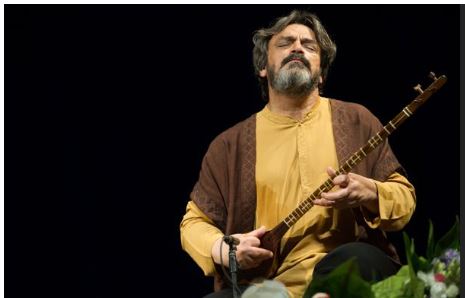

Fig 4: Mohammad Reza Lotfi

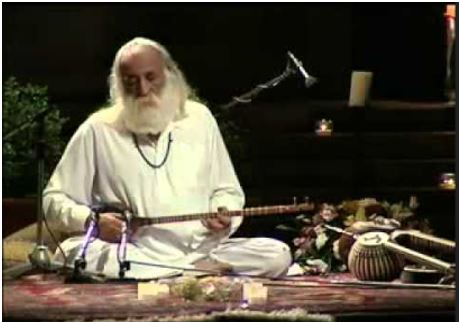

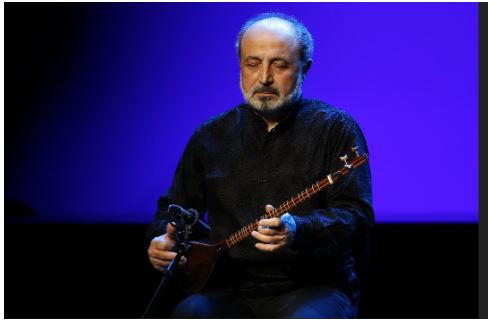

Fig 5: Hossein Alizadeh,

Fig 6: Massoud Shoari

Fig 7: Dariush Talai

Works Cited

“All about Persian Setar.” Sala Muzik, salamuzik.com/blogs/news/all-about-persian-setar. Accessed 26 Nov. 2023.

https://salamuzik.com/blogs/news/all-about-persian-setar

Ardalan, Afshin. “Persian music meets West.” (2012). https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/38067249.pdf

Instrument Details, “Setar.” Farabi School,

http://farabisoft.com/pages/farabischool/instrumentsdetails.aspx?lang=en&PID=4&SID=31

Mansour, Hossein, Gary Scavone, and Vincent Freour. “A comparison of vibration analysis techniques applied to the Persian setar.” Acoustics 2012. 2012.

http://www.music.mcgill.ca/caml/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=publications:nantes2012_mansour.pdf

Pedrammehr, Siamak, et al. “A study on vibration of Setar: stringed Persian musical instrument.” Journal of Vibroengineering 20.7 (2018): 2680-2689. https://www.extrica.com/article/19505#:~:text=This%20instrument%20is%20a%20member,plectrum%20to%20strum%20the%20strings.

Taghavi, K. “The Setar: Supreme in Persian classical music.” Center for World Music, 1 June 2015, centerforworldmusic.org/2015/06/world-music-instruments-the-setar/.

Week Lecture 3- https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/10_DmjpAcozlktW_rGfrXjkIGXvC0NB76/edit#slide=id.p1

Delivering a high-quality product at a reasonable price is not enough anymore.

That’s why we have developed 5 beneficial guarantees that will make your experience with our service enjoyable, easy, and safe.

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more